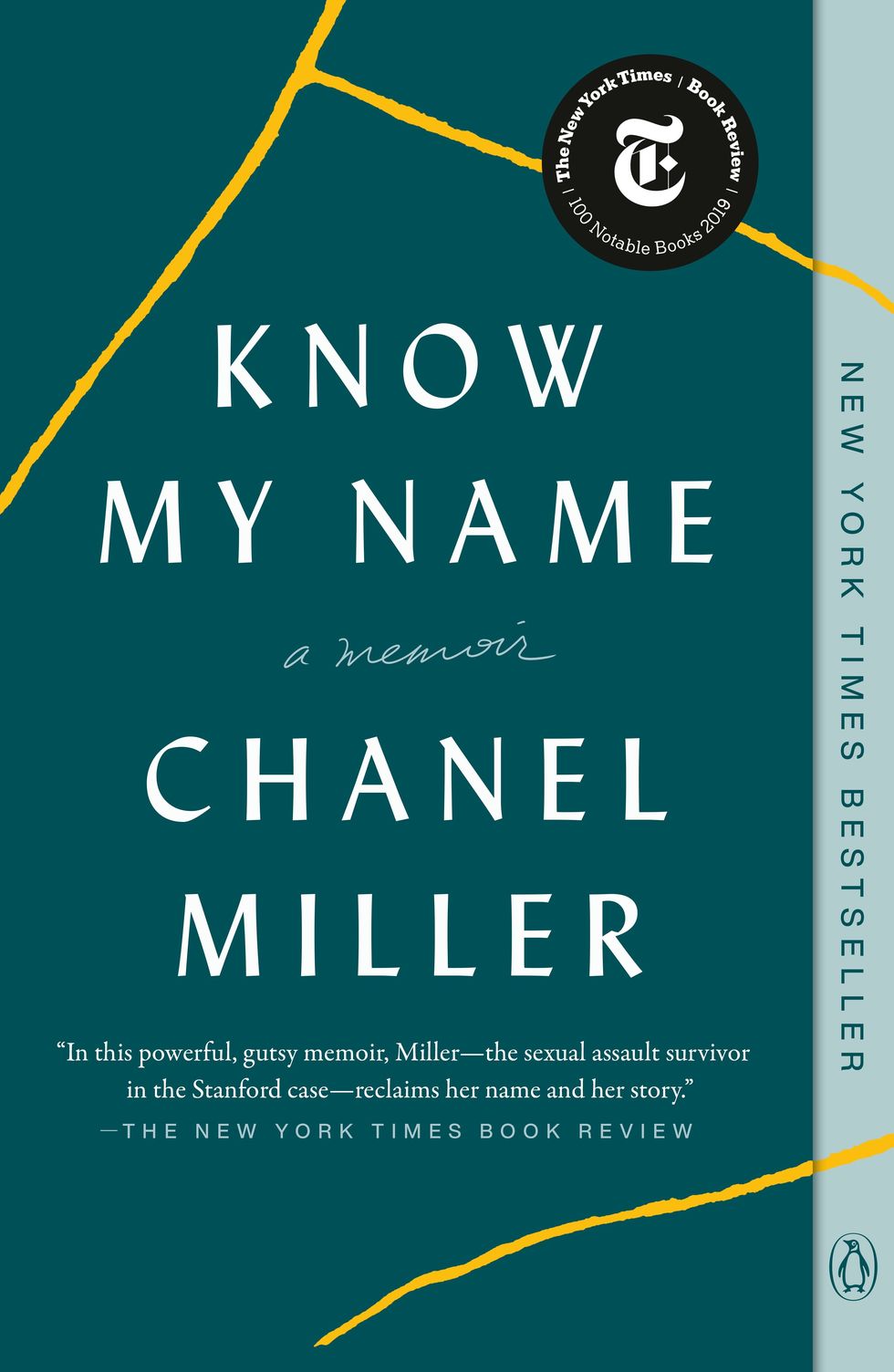

In 2016, millions came to know Chanel Miller through the impact statement she read at the Stanford sexual assault case against Brock Turner; though anonymous at the time, her letter was posted on BuzzFeed and promptly went viral. Then in 2019, Miller published her award-winning memoir Know My Name, reintroducing herself and filling in the details of who she is: a now-28-year-old Chinese-American woman who had a story to tell.

For anyone who read the book, or followed Miller’s work after its publication, it was clear that she's also an artist. When she published Know My Name, she released a companion video featuring her illustrations; her comics populate her Instagram page.

Now, she’s debuting her first official museum exhibit, the triptych mural I was, I am, I will be at the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco. While the museum is currently closed to the public due to the pandemic, Miller’s art will be visible day and night from outside the gallery.

More From ELLE

Chatting with ELLE.com from her home in New York—she moved the weekend before the city went into lockdown—Miller discusses what the art piece represents to her and why drawing is her socially acceptable form of rage.

How did this collaboration come to be?

Abby Chen, the curator, is the one who reached out. They were in the middle of building this gallery. It's wonderful because they brought me on without knowing what I would create, without knowing what the space would look like yet. My greatest fear upon releasing my name was that I'd be pigeonholed as a victim, that I would not be able to transcend my story and be truly seen for what I love to do, which is drawing and writing about all kinds of things. The fact that they came to me and gave me the space and the platform to say, "Continue to tell us who you are beyond this story," meant a lot.

I had grown up going to that museum. It's important to me that this is being shown where I consider home. I remember during the trial, flying into the San Francisco airport, there was always this feeling of dread. My home became synonymous with anxiety, and I was obsessed with staying anonymous. The fact that I can debut my art, and it's something that came directly from me and it's more playful and allows for an experience between viewers, is healing for me to see.

What was the process of coming up with the triptych? Was it an idea you always had?

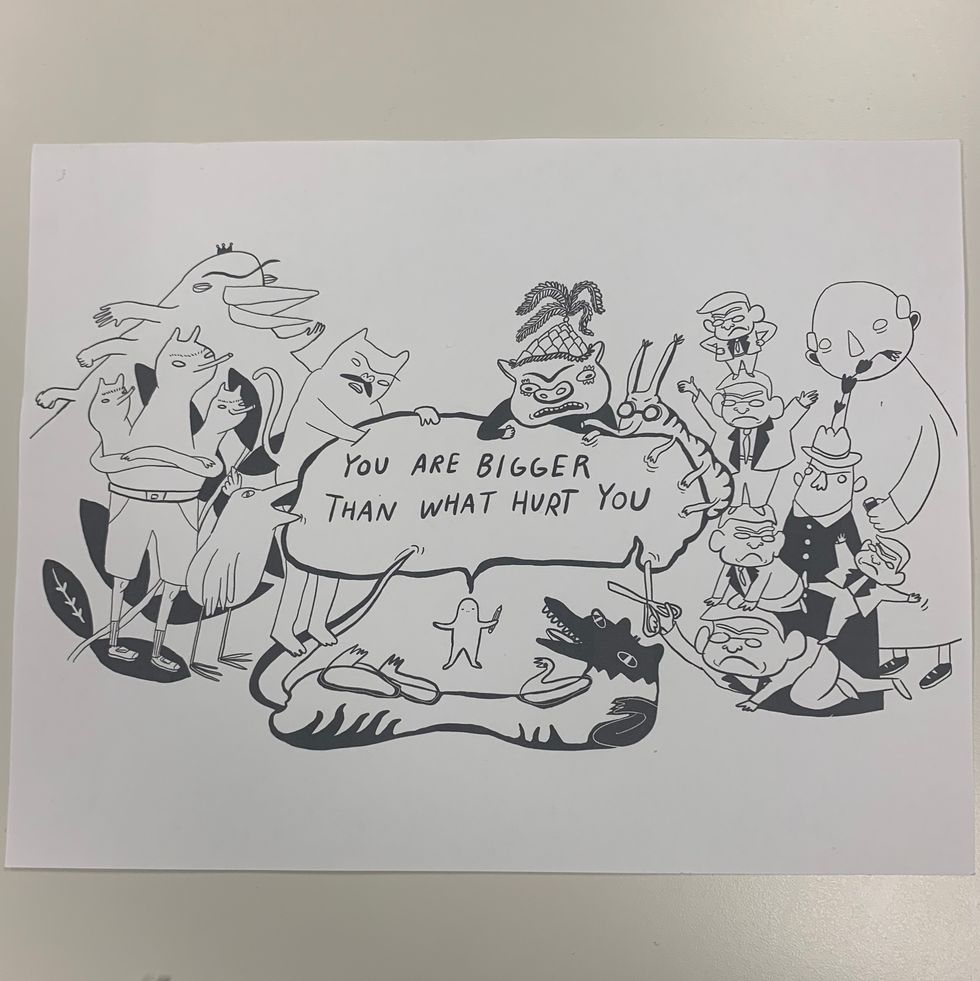

I've never been given a scale this big to work on. I thought it was going to be one wall. The original idea was actually the phrase, "You are bigger than what hurt you." I had a very small character who was the protagonist of the piece who was going to be surrounded by these oppressive, menacing creatures. I liked that the power of the little creature was that it didn't feel a need to make itself large or violent or to push back. It just simply stood in its power with its message.

But once I understood there was going to be three panels, that got me thinking about creating more of a narrative. For this piece, I like that from the street you do not have to read it from left to right because you could be walking either way on the sidewalk. It's not past, present, future. It's the fact that, in the present, there are many times we may repeat patterns from the past. We may fall into old states or old memories may resurface in the present that we are forced to reckon with. I think that's all a part of healing, being able to incorporate and revisit the past while also being able to keep moving and envision yourself in the future. The message is that everything is ongoing and that we're always in transition and there's no correct state of being.

Admittedly, when I saw the piece, the “I will be” sentence felt intimidating since everything feels so unpredictable right now. How do you personally stay grounded in the “I am”?

When I was waiting for trial and court dates kept changing, I realized I had to figure out how to cope with uncertainty. In the book, I call all of my plans "sugar cube ideas" and the case was a pot of hot water. Every time I tried to make plans, I'd have to change them because court dominated my schedule. I had to just surrender to not knowing. And there's a lot of that happening now.

I think it can be really difficult to feel like you don't have solid ground to walk on. I know for me, grounding techniques, I would focus on concrete things, my concrete surroundings. Any time I felt like I was floating or unanchored from myself, I would come back into the present by observing the light in the room or the texture of my shirt or feeling my feet flat pressed to the ground. Those are all ways of coming back to myself.

You're an artist, but so many people were introduced to you as a writer. Did you always know that Know My Name would be a book, or did you ever consider presenting that story in a different format?

One thing I struggled with during the assault was the graphic nature of it and the images that existed. The photographs of my body were ones I was never comfortable bringing to light. I felt like, when I was approaching the story of my assault, words were going to be the safest way I could do that. Words are still extremely powerful and capable of constructing imagery for the reader without having to sacrifice my dignity. To me, bringing you in to see what I saw was more about bringing you into my internal landscape and how it felt.

Because my story had already been laid out in so many news articles and court transcripts, it already existed in words, but the words were never mine. I felt it was important to assert my narrative and give it a fighting chance against the rest and leave it to everyone to decide which narrative rung the most true.

Your book is also being translated into Chinese. Unfortunately, we've all seen Trump call COVID-19 the Chinese virus and the reports of anti-Asian racism across the country. How has that affected you and your family?

It's the omnipresent fear and tension that something could happen at any time—just that heightened sense of vulnerability, being on the defense when you're walking down the street, not being able to trust how you will be perceived. I was traveling a lot earlier in the year and started wearing a mask in February. I would be the only one on the airplane wearing a mask, and it felt humiliating. When I would get to my row, I just worried that the person would look up and be disappointed that I was the one sitting next to them or be fearful. It was really exhausting to be worrying about being perceived as contaminated. It's strange because my sense of self would dwindle when I traveled. I would get to an event where I would be given a platform and be celebrated and treated with respect. But as soon as I got back on the plane and was the only one wearing a mask, it felt isolating.

You've been very vocal in your support for the Black Lives Matter movement. How do you view art as a tool for allyship?

I'm understanding the power of having a platform. I think, with all the injustice happening, being able to draw something and present something that addresses what's happening is like my socially acceptable form of rage. In drawings, you can be more graphic and loud and direct in ways that I never felt like I could be in person. I think it's more freeing, and you can rope more people into the cause when you do it creatively.

I think it's the artist's duty to redirect attention. So many of us are obsessed with returning to normalcy, which does not exist and is not an option. I think it's an artist job to keep resurfacing things we may not want to take a hard look at in favor of the ease of daily life and the comfort of the illusion of normalcy.

In recent comics, you've touched on the difficulty of being productive during the pandemic. What has your relationship to creativity been like recently?

I will spiral if I don't actively reconnect to others, and right now, you can get away with not connecting for longer periods of time. As soon as I'm hard on myself, if I can express that in a drawing and share it, I know that it will resonate. It's such a comfort to me that, even in my lowest lows, that feeling can still connect me to someone because there's someone else sitting in their lowest low. I always go back to the belief that what is unbearable is not these hard feelings—what’s unbearable is feeling them alone. If I can continue to connect my hard feelings with other people's hard feelings, then we can move forward together.

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

Madison is a senior writer/editor at ELLE.com, covering news, politics, and culture. When she's not on the internet, you can most likely find her taking a nap or eating banana bread.