The Corbetts had one of the biggest lawns in the cul-de-sac. One Saturday, after David Fritzsche finished mowing his own lawn, he walked over to help Jason Corbett with his. Afterward, the neighbors grabbed chairs and sat in the driveway. Kids flitted in and out, their wives dropped by to chat, and each man drank several beers as afternoon turned to evening. The “driveway social” that unfolded on August 1, 2015, wasn’t uncommon in Meadowlands, a close-knit subdivision in North Carolina. When Jason’s in-laws arrived around 8:30, the Fritzsches went out for dinner and the Corbetts ordered pizza.

Before dawn, Jason was dead. The fatal altercation involved his wife, Molly Martens Corbett, and her 65-year-old father, former FBI agent Thomas “Tom” Martens, who, according to an appeals court judgment in the case, came upon Jason strangling Molly, threatening to kill her, and refusing to let go despite Tom’s pleas. In the ensuing fight, Tom used a Little League bat and Molly struck Jason with a brick landscaping paver. Though they claimed self-defense, father and daughter were convicted of second-degree murder in 2017.

Last year, the North Carolina Court of Appeals overturned their convictions and ordered a new trial, in part because, among other errors, evidence that Jason may have abused Molly was excluded from the first trial. The state appealed, but on March 12, 2021, the North Carolina Supreme Court upheld the appellate court judgment.

Meanwhile, another trial of sorts is playing out in the divided Meadowlands neighborhood where Molly is seen as either a victim of abuse, who lost nearly everything fighting for her life, or a murderer who robbed two children of their father. Questions never answered by the first trial have been reignited by the second, and a closer look at life inside that brick house with the big yard could prove essential to understanding the events on the morning of August 2, 2015. But what happens when an allegation brings domestic violence into the harsh light of public scrutiny, particularly when people aren’t always who they seem to be?

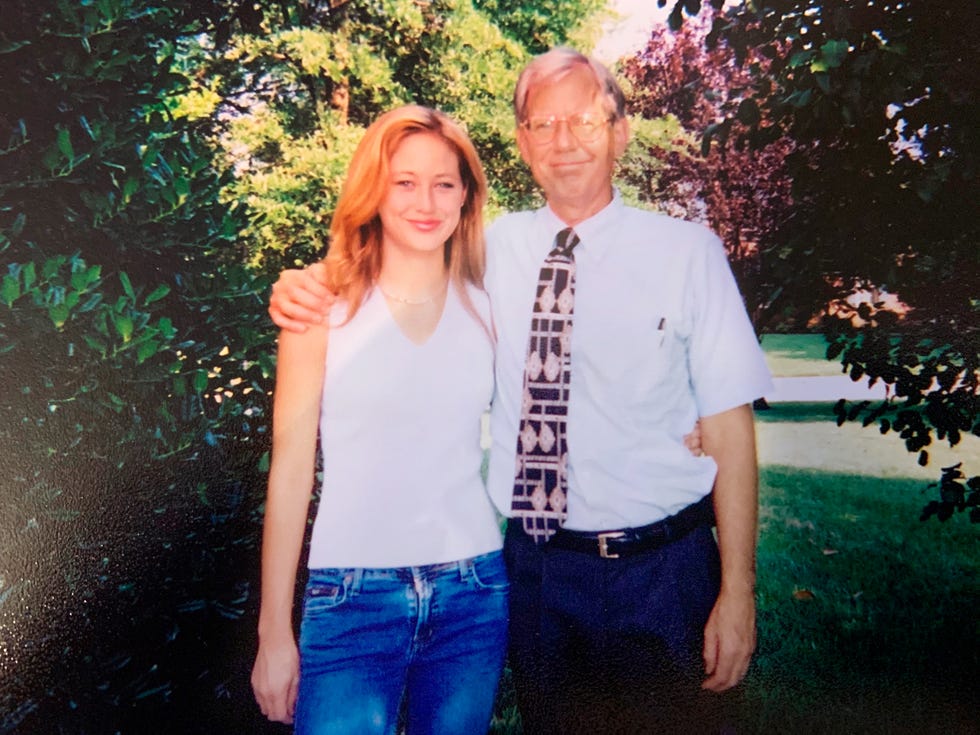

It was only meant to be a job, and she took it on a whim. At 24, Molly Martens moved to Limerick, Ireland, to work as a live-in nanny for Jason Corbett, a 32-year-old widower, taking care of his children, Jack, three and a half, and Sarah, one and a half, after his wife, Margaret “Mags” Corbett, died suddenly when Sarah was just a few months old. A romantic relationship developed between Jason and Molly almost immediately. “I really hope that you are as happy as I am to have met and fallen (jumped) in love with you,” Jason emailed Molly a few weeks after she stepped off the plane in cowboy boots.

Molly grew up primarily in Knoxville, Tennessee, the second of four children and the only girl. Family members describe her as smart, sociable, and stubborn. When Tom coached her childhood soccer team, Molly was often too busy singing and dancing with friends to focus on the ball. A voracious reader, as a teenager she would stop by her mom’s book club to share her opinion.

After briefly attending Clemson University (she dropped out due to mononucleosis), Molly took some community college classes, worked a series of entry-level jobs, and lived “in the condo with the fiesta lights on all year,” according to the dating profile that caught Keith Maginn’s eye in 2007. Over the course of a year, she became pregnant, suffered a miscarriage, and got engaged to Keith.

In March 2008, Molly moved to Ireland. Keith and Molly disagree over whether they were still together. Either way, the nanny job came at a pivotal time. She had struggled with feelings of inadequacy after dropping out of college and “not knowing what I wanted or who I was,” so she says it felt amazing when she made Jason “feel whole again” and found purpose in two children who needed her. “I fell in love with that feeling, and I fell in love with Jason,” she tells me.

Raised in a working-class family in Limerick and one of eight children, Jason was “confident,” popular, and “very ambitious, even at a young age,” according to his older sister Marilyn Corbett. He worked his way up, promotion after promotion, from machine operator to plant manager of an international packaging company. “I don’t care if he was with the president of a multibillion-dollar private equity fund or a third-shift janitor who’d been with the organization two weeks, he treated them the same,” says John Hartwell, his former boss. Claire Delap, who also knew Jason’s first wife, describes him as an attentive friend who tried to make the most of every day. She remembers his “great old laugh” and the time he showed up at the maternity hospital with a little pink jacket he picked out for her newborn.

Molly had played the role of caretaker since she was a toddler lugging around Big Boy, a doll nearly her size. She doted on her brothers, babysat neighborhood kids, and looked after younger relatives with such care that her aunt considered making a shirt emblazoned with “Everybody’s Favorite Cousin.” But in Limerick, she found herself in a new role: Soon after she arrived, Sarah was calling her Mommy, and Jack followed suit.

Jason and Molly got engaged on Valentine’s Day 2010, and married in her hometown on a scorching-hot day in June of 2011. They moved to North Carolina that summer, as Jason was able to transfer, assuming a demanding role at an underperforming packaging plant. Molly took care of the children, volunteered at their school, and coached a children’s swim team in Meadowlands.

In the week after their father’s death, Jack and Sarah, then 10 and 8, were each interviewed twice by authorities in North Carolina. They described “Jason’s worsening anger management issues; Molly and Jason’s ongoing relationship troubles, including alleged verbal, emotional, and physical abuse; and, perhaps most importantly, [their] awareness and perception of these issues,” according to the appellate court judgment.

On August 2, still wearing her pajamas, Molly gave an interview at the Davidson County Sheriff’s Office and alleged that Jason had abused her. She said she’d been to the hospital a few times, but hadn’t revealed what caused the injuries. Molly has an abnormal tangle of blood vessels on her left foot; she alleged that Jason would “accidentally on purpose” step on her left foot when he was angry. She also claimed Jason was verbally and emotionally abusive.

According to Molly, during her relationship with Jason, there were heartfelt apologies, the possibility that things would improve, and abuse that came in waves, worsening over time. Through it all, Molly says her love of Jack and Sarah kept her from leaving Jason. But he never followed through on his promise to let Molly adopt the kids as part of the wedding ceremony or afterward. During her interview at the sheriff’s office on the 2nd, when asked if she’d ever told the police about the alleged abuse, Molly answered, “No, because the children aren’t biologically mine, and they’re not citizens, and so he could take them away.”

Both Molly and Jason consulted lawyers with questions about custody during their marriage. According to an investigative interview summary with a senior employee at Jason’s company, in 2013, Jason was adamant that he didn’t want to use Molly’s citizenship to arrange a visa because “he did not want [her] to have any legal grounds to maintain custody” if they later divorced. According to Molly, Jason used her vulnerability as a nonlegal, nonbiological parent to maintain power over her.

“I felt like I could make it,” Molly says of her plan to stay until both kids were old enough that a judge would consider their opinions on custody arrangements. “I realize, looking back now, that it was a whole lot worse than I thought it was. And I think that’s true for a lot of domestic violence situations. You just convince yourself, ‘Oh, it’s not that bad.’ Because you wake up in the morning and you have to keep living life. You have to go to work and you have to pack the lunches and you have to clean the kitchen, and so you’ve convinced yourself that ‘Oh, I was strangled last night, but I’m okay.’ ”

The specter of domestic violence hung over the Corbett house well before Jason’s death. After Molly confided in a few friends, the Corbetts’ neighbors watched the couple closely. For some in Meadowlands, it seems a lack of visible evidence and Molly and Jason’s failure to fit expectations of how abuse victims and perpetrators look and act made it harder to believe the allegations were true. To a lot of his neighbors, Jason was a great guy. According to the summary of an interview prosecutors conducted with a neighbor and friend of the Corbetts, after hearing about the allegation, he didn’t see signs in Jason nor bruises on Molly, and “contrary to [the] expected behavior of [an] abused spouse,” Molly was “very open” with others around, made jokes about Jason, and never seemed frightened of him.

When it comes to domestic violence, stereotypes impact more than who gets believed—they shape how blame is apportioned. A 2008 study published in the journal Sex Roles found “when the victim [of severe psychological abuse] was nontraditional or she reacted negatively to the abuse (e.g., yelled back), she was rated more negatively and blamed more due to her lack of warmth.” In Meadowlands, it appears other things Molly shared also influenced how people interpreted the abuse allegation. The Corbetts’ next-door neighbors reported that Molly “would say things that did not add up,” according to the prosecutors’ interview summary.

“First of all, everybody lies, that’s true,” Molly says when I broach the subject. “And anybody who says that they don’t, they’re lying.” But “if you had to ask me what I am most ashamed of in my life, it would be the times that I have not been honest with people.” Molly acknowledges she’s “said things to make myself sound better because I’m ashamed of who I am or aspects of who I am.”

Molly claims there were times when she lied because Jason had done so first. He didn’t want people to know that they met when she was his nanny, according to Molly, so the first time they went to a dinner party in their new neighborhood, he made something up. “When that becomes the truth, then you have to develop a backstory and adjectives that go with it,” she says. According to Molly, that’s why people thought she’d been an editor in Ireland rather than Jason’s nanny. But other stories are harder to understand.

According to a sheriff’s report, her freshman year roommate said that Molly kept a framed photo of her little sister, whom she said had died of cancer. But after visiting the Martens household and not seeing any photos of the little girl, Molly’s roommate “looked at the picture closer and noticed a ‘5x7’ in the corner of the photograph, meaning it was a standard photograph of a model that comes with the frame when it is purchased,” the detective wrote.

Molly says she could have said something like that as a way to relate to someone, then gotten caught in a lie she didn’t mean to tell, but “there’s no excuse.” She insists she didn’t have any framed photographs in her dorm room, but with a collage of photos and magazine tear-outs on her walls, it’s possible she referred to someone pictured as a younger sister who died. Six years later, according to an email Molly sent Jason after what she described as a betrayal on his part, she wrote, “other than my sister’s death nothing has ever devastated me so much.” This email was in investigative records. Molly didn’t remember writing it. She now acknowledges she never had a sister.

During one of our many interviews, I ask Molly if, looking back, she thinks she had an issue with lying. At first she says, “I think that I did,” before adding, “I don’t think I do now.” But then she expresses uncertainty. “I don’t think I did necessarily more than the average person, it’s just everything that I’ve ever said and done [has] come to light,” she says. “I have a hard time thinking about myself doing those things, and I feel very regretful.”

When I mention to Molly what her neighbors told authorities—that she’d described giving birth at book club or Bible study—she says she didn’t talk about labor, but about pregnancy, which she has experienced. “I’m sure that there’s a possibility that I led people to believe that was directly related to my children or one of my children,” she says. “But that is an interpretation.”

On a subsequent call, Molly acknowledges that she may have gone further than describing pregnancy, admitting she “could have said that Sarah was biologically [hers].” While a neighbor told authorities that close friends knew Molly wasn’t Sarah’s biological mom, what she might have told other neighbors wasn’t just a lie, but also her most desperate wish—to be a mother in the eyes of the law so she could leave Jason and not lose the children.

Two people walked out of the Corbetts’ master bedroom in the early hours of August 2, 2015, and during the trial that unfolded two years later, prosecutors suggested they were a pair of murderers. Per the appellate judgment, Tom said he woke up late in the night to noises, including “a scream and loud voices” coming from above the guest bedroom, scrambled out of bed, grabbed the Little League bat he brought for his grandson, and rushed upstairs.

On the stand, he described the moment he opened the door to the master bedroom. The picture remained “frozen” in his mind—Jason’s hands around Molly’s neck, the couple turning toward him, surprise registering on their faces. When Jason refused to let go, repeatedly insisting he was going to kill Molly, father and daughter fought for survival. Tom cried on the stand as he described seeing Molly go from “wiggling” to “limp” while Jason dragged her in a “tight choke hold” toward the master bath. Tom testified that some of his initial strikes with the bat didn’t seem to do anything beyond “further enrag[ing]” Jason, who later knocked him to the floor. Tom kept hitting Jason “until I considered the threat to be over,” according to his testimony, which occurred when Jason “went down.”

A few weeks before his death, according to a nurse’s testimony, Jason said “he had been more stressed and angry lately for no reason.” Molly didn’t testify, and the recorded interview she gave at the sheriff’s office wasn’t shown to jurors, but according to her written statement, which was introduced at trial and reproduced in the appellate judgment, when Jason grabbed the bat from her dad, she “tried to hit him with a brick (garden decor) I had on my nightstand.”

The state would offer a different narrative, one that didn’t include strangulation or self-defense. The prosecution “relied heavily upon forensic evidence, including photographs of Jason’s body and the undeniably violent fight scene,” the appellate court noted. According to the forensic pathologist, Jason suffered a minimum of 12 blows to the head and “the degree of skull fractures in this case are the types of injuries that we may see in falls from great heights or in car crashes.” One juror vomited when a photograph of Jason’s skull was shown. The state called an expert in bloodstain pattern analysis; among other things, he testified that Jason was “descending” to the floor as he was being hit. (When three jurors sat for a post-trial interview on 20/20, the host asserted that the crime scene photos, combined with the expert testimony, “sold” jurors on “the prosecution’s overkill theory.”)

The state suggested in its closing argument that Tom and Molly delayed calling 911 and came up with their story “while Jason’s body was cooling.” The jury voted to convict Tom immediately. Within a few hours, they also found Molly guilty. Father and daughter were sentenced to 20 to 25 years each on the charge of second-degree murder.

But Molly and Tom’s legal fight didn’t end with their guilty verdicts. In the 20/20 interview, the TV host revealed to jurors that Molly claimed Jason was abusive. “Where’s the evidence?” a juror asked. “The defense did not once suggest any of that.” Aside from the strangulation allegation, domestic violence came up only briefly at the trial. Tom testified that he found Jason to be very controlling of Molly, that he’d seen bruises and he wasn’t sure what caused them, and acknowledged he never saw Jason physically abuse her until the night of his death.

According to the Irish Times, the jury foreman shared the “first question everybody had in their mind” when they began deliberating: Why did Molly have a paving brick on her nightstand? What jurors hadn’t seen were interviews of the Corbett children conducted shortly after Jason’s death, providing not only evidence of domestic abuse and details about the night Jason died, but also an answer to the jury’s question about the landscaping paver. Apparently meant for a craft project, it was brought inside because of rain.

After returning to live in Ireland with Jason’s family, the children recanted things they said about their parents’ relationship. The children’s statements and their recantations have been subject to intense debate, with the trial judge excluding them and the appellate court finding that decision incorrect, noting that critical details relevant to the night of Jason’s death were “never recanted.” The trial judge’s ruling on the children’s statement was one of several issues that came up on appeal. According to the appellate court, the trial judge allowed testimony about critically important bloodstains that “bolstered the State’s case” by showing “defendants administered blows while Jason was down on the ground and defenseless,” even though it was “based upon insufficient facts and data” and not “the product of reliable principles and methods.”

In a split decision, the appellate court ruled that the exclusion of certain evidence, and erroneous inclusion of other evidence, meant Tom and Molly were “prevented from presenting a meaningful defense” or receiving “the full benefit” of their self-defense claims, and, in turn, the jury was “denied critical evidence and rendered incapable of performing its constitutional function.” The North Carolina Supreme Court affirmed the appellate court’s ruling and granted a new trial. Tom and Molly remain incarcerated.

Women who’ve been abused “enter the courtroom at a disadvantage,” Leigh Goodmark writes in the Yale Journal of Law and Feminism, citing research that shows women are “generally perceived as less credible than men (and occasionally, as no more credible than children).” A failure to conform to expectations further disadvantages victims of domestic violence. In the U.S., “the public, the media, and the legal system have coalesced around a stereotypical image of victims of domestic violence,” according to Goodmark. She is “a passive, middle-class, white woman cowering in the corner as her enraged husband prepares to beat her again.”

Victims who don’t look like this experience the consequences of this constricting stereotype. They may be denied support and services or face high-stakes legal proceedings wherein they tell a true story others find hard to believe, impacting custody, protective orders, or criminal cases. A woman who fights back against her abuser, Goodmark writes, “simply is not a victim in the eyes of many in the legal system.”

A new trial would give Molly another opportunity to testify. But how she adheres to the archetype of a domestic abuse victim could impact whether jurors believe her. And if she testifies, the stories she’s told in the past might threaten her credibility. When a defendant has a history of being less than truthful, if they testify, “it’s not that it could come up—it will come up,” says Donald H. Beskind, a law professor at the Duke University School of Law, who has not reviewed Molly’s case.

While it’s possible to discount Molly’s allegation of abuse as another one of her stories—“a complete fabrication” by her and her family to get away with murder, as Jason’s sister Tracey Corbett-Lynch puts it—there is compelling evidence that Jason was not just the “gentle giant” he’s routinely described to have been. And it doesn’t rely on Molly’s word or the children’s initial statements.

Years ago, fearing no one would believe that Jason was abusive, and at the advice of a custody lawyer, Molly says she began using hidden recording devices. Molly says many of the recordings have been destroyed or lost, but the few that remain were given to the district attorney’s office. David Freedman, who represented her early on, says “to the best of [his] recollection” that’s the case. While I compared the audio provided to other audio of Molly, Jason, and the children, there was no way for me to determine exactly when they were made or under what circumstances.

On a recording titled “Jason Comes Home Late. Dec. 2013,” he finds the door locked and rings the bell repeatedly. She opens it within 39 seconds and apologizes. “You never mean to do anything, do ye?” he asks angrily, then mocks her. Molly pleads, multiple smacking sounds can be heard, and she begins to whimper. “I hate you,” she sobs quietly before the recording cuts out. She says Jason had a key, but was too drunk to get the door open, and, as often happened in their home, “the fury would just rise and rise and rise until whatever was going on was all my fault.”

Molly describes developing a physical reaction to Jason’s touch. In an argument that unfolded after Jason found out she’d been recording him, he accused Molly of acting like he was “some sort of demon,” and she said, “I can’t help being scared. I’m really sorry that I’ve been scared.” When he brushed off her apology, she added, “If you think the scariness is gonna go away with you hitting me on the head or throwing things at me in the back”—and Jason interrupted with a “Yeah, okay, okay, whatever.” A psychiatrist later found Molly had “serious symptoms” of PTSD, according to an evaluation provided by her lawyer with her consent. While some Meadowlands residents doubted her, there were neighbors who believed Molly’s abuse allegation, including one who emailed the DA’s office, writing that she was “confident in saying that everything [she] saw supported the fact that the abuse was real,” according to investigative records.

“When the kids were younger, I used to just tell them that people fight all the time.... It’s not the right way to deal with things, but it doesn’t mean that Daddy doesn’t love me or that I don’t love Daddy, or we don’t love you,” Molly says. But eventually she changed her messaging. I cannot keep telling them this, she thought. I cannot let them think this is normal.

When Molly went to the sheriff’s office in the early hours of August 2 for a voluntary interview, she said Sarah had had a nightmare and thought the fairies on her sheets were bugs and lizards. As the appellate court noted, a crime scene photo from the trial shows what looks to be a pile of fairy sheets at the foot of Sarah’s bed. The North Carolina Supreme Court found that Sarah’s interview “describing her nightmare and her entry into the master bedroom provided compelling firsthand evidence supporting defendants’ account of how the altercation began” and “confirmed…Jason was angry when the altercation began.”

Before being sentenced, Molly said, “The incidents of August 2 happened in a way that they happened on a somewhat regular basis; the difference is that my father was there.” While Tom had testified to her surprise when he opened the bedroom door, Molly described a different feeling. To a friend, she wrote, “What I remember most about that night is how humiliated I felt when my father opened that door and saw me being strangled.”

In 1868, the North Carolina Supreme Court offered a powerful ruling on domestic abuse. A husband had given his wife three lashes. “The violence complained of would without question have constituted a battery if the subject of it had not been the defendant’s wife,” the court wrote. But however “great are the evils” of temporary pain inflicted inside the home, “raising the curtain” and airing what goes on inside the home would be worse. A family, like the state, has its own governance, and unless “permanent or malicious injury is inflicted or threatened,” the state should not intervene, the court said.

While the state plays a more active role in domestic affairs today, there’s an assumption that even without raising the curtain, it’s possible to know what goes on inside a home. People imagine an abuser would be easily recognizable, not a beloved neighbor. It’s more comforting to believe that violence next door would be obvious than it is to live with the unsettling reality that this isn’t always true.

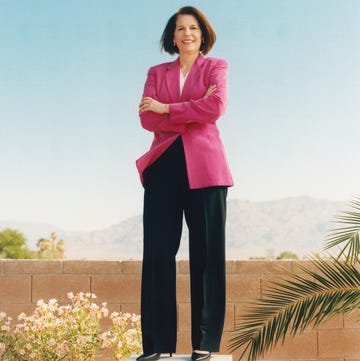

When researching her book No Visible Bruises: What We Don’t Know About Domestic Violence Can Kill Us, Rachel Louise Snyder spent time at treatment programs for abusers, finding herself disconcerted by “how incredibly normal they all seem.” David Adams, credited with creating the first batterer intervention program in the U.S., told her that only about 25 percent of abusers are “rageaholics.” Instead, most target their anger quite specifically, and thus the abuse can be a surprise to people who know them. “The average batterer is pretty likable,” he told Snyder.

Molly is well aware of how she and Jason appeared. “In addition to my husband being so likable and jolly, I did not come across as a victim,” she wrote to a friend after his death. Instead of looking “subservient” or “afraid,” she was “social and talkative and outgoing.”

When it comes to assessing Molly and Jason’s relationship, it’s not just the story Molly tells, but the one we tell ourselves about what domestic violence looks like, who abuses and is abused, and how clear this would be to outsiders. It’s a story with little room for flawed or unreliable victims. “No one is a hero or a villain; we’re all somewhere in between,” Molly says. “But when you’re looking for characteristics to define someone at either side of the spectrum, you’re going to find them.” She points out that if you put aside the good and just focus on the bad, or vice versa, you don’t really see the person in front of you. “That’s a character,” she says. “It’s not real.”

This story appears in the May 2021 issue.

Alex Ronan is a writer and reporter from New York.